Abraham Johannes Muste, born on January 8, 1885, died on February 11, 1967. Known to the public as A.J. Muste and to his friends and associates simply as "A.J.," he was a remarkable and in some ways enigmatic figure bridging the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Born in Holland, he was brought to the U.S. as a child of six and raised by a Republican family in the strict Calvinist traditions of the Dutch Reformed Church. In 1909 he was ordained a minister in that church, and married Anna Huizenga, with whom he was to share the next 40 years and raise three children. In the normal course of events Muste would have lived out his life within those conservative limits, perhaps with theological distinction, but without great impact on the temporal world. His record at the time of his ordination: class valedictorian at Hope College, captain of the basketball team, a magna cum laude degree from Union Theological Seminary.

Yet, A.J. soon made a decision that would begin a lifetime of carefully considered radical activism. In the 1912 presidential election he cast his vote for Eugene Victor Debs. In 1914, increasingly uncomfortable with the Reformed Church, he became pastor of a Congregational Church. When war broke out in Europe, A.J. became a pacifist, inspired by the Christian mysticism of the Quakers. Three years later these beliefs cost him his church. He then started working with the fledging American Civil Liberties Union in Boston, and took a church post with the Friends in Providence. In 1919, when the textile industry strikers appealed for help from the religious community, he suddenly found himself thrust into the center of the great labor strikes in Lawrence, Massachusetts. In the early 1920s A.J. became director of the Brookwood Labor College in Katonah, New York. This school was of enormous importance in labor history; its curriculum consisted of the theory and practice of labor militancy--so much so that the American Federation of Labor found Brookwood Labor College a considerable embarrassment. The young Dutch Reformed minister had become a respected--and controversial--figure in the trade union movement.

For several years during the 1920s he served as Chairman of the Fellowship of Reconciliation but steadily drifted toward revolutionary politics, and in 1929 he helped form the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA), seeking to reform the AF of L from within. When the Depression broke like a storm over America, the CPLA became openly revolutionary and was instrumental in forming the American Workers Party in 1933--a "democratically organized revolutionary party" in which A.J. played the leading role.

A.J. had now completed one stage of his evolution, from conservative young pastor to revolutionary American Marxist. He abandoned his Christian pacifism and became an avowed Marxist-Leninist. He was a key figure in organizing the sit-down strikes of the 1930s and, cooperating with James Cannon of the Trotskyist movement, he merged his own political group with Cannon's, forming the Trotskyist Workers Party of America.

At this point something occurred in A.J.'s life which cannot be fully explained. In 1936, troubled by certain questions regarding revolutionary activity, he took a ship to Europe, where, in Norway, he met with Leon Trotsky. He had left the U.S. as a Marxist-Leninist, but returned that same year as a Christian pacifist. It is not clear what caused the religious experience he had on the trip, but he was deeply changed. For the second time in his life, A.J. burned his bridges behind him, although he did remain active in the labor movement, heading the Presbyterian Labor Temple on 14th Street in Manhattan. In 1940 he became Executive Secretary of the religious pacifist organization, Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), a post he held until 1953.

The period from 1940 to 1953 was, in its own way, as turbulent as the 1930s. It covered the war years, the beginning of the Cold War, the McCarthy period. Under A.J.'s leadership, FOR stimulated the organization of the Congress on Racial Equality, the first of the militant civil rights groups. At the age of 68 A.J. "retired." The year was 1953 and for most persons life would have been filled with enough risk, enough drama, to permit settling into a respected twilight period. He had lived through the Depression as a major radical leader, heavily influenced the labor movement, and had opposed two world wars. He had rallied American pacifists in their darkest hours of World War II, defending young men who refused military service, fighting complex theological battles with those who sought to place the moral weight of Christianity at the disposal of the State. Yet, he remained virtually unknown to the general public. He was considered by those who worked with him to have one of the sharpest political minds in America. But it was an almost perversely prophetic mind, taking him always one step beyond the point the general public--or even his followers--was prepared to go. His associates learned from him directly--from discussions, the dialogues, and actions which marked their relationships with him. He wrote several books, but he communicated--and influenced--best on a personal level.

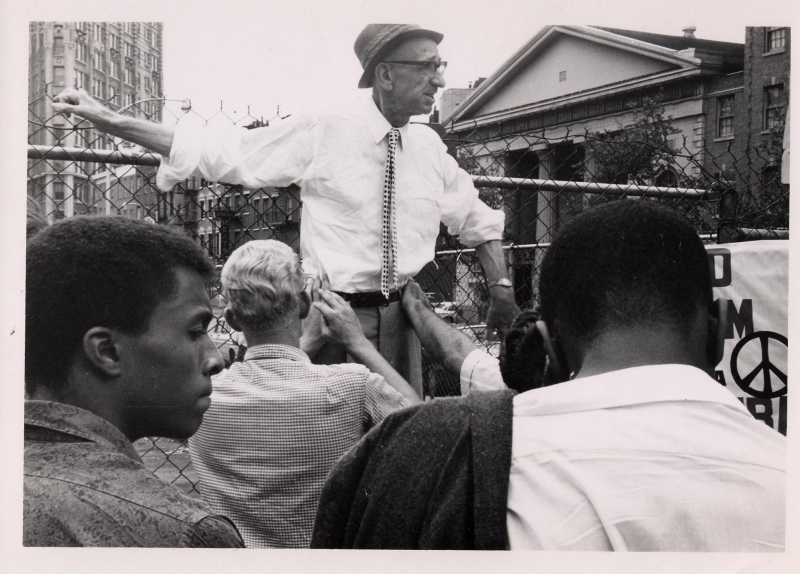

A.J.'s life after retirement was not rich with honors but with action. He continued for nearly another twenty years to trouble the society around him. He became the leader of the Committee for Nonviolent Action, an organization whose members sailed ships into nuclear test zones in the Pacific, hopped barbed wire fences into nuclear installations in this country, and went out in rowboats to try to block the launching of American nuclear submarines. In 1961 a team of pacifists completed an extraordinary walk all the way from San Francisco to Moscow, and thanks largely to the diplomacy of A.J., was able to carry the message of unilateral disarmament not only to towns all across the country, but even into Moscow's Red Square.

A.J. was close to the emerging liberation movements in Africa, and helped organize the World Peace Brigade which worked closely with Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania. African leaders often met first with A.J. on their visits to this country--and only later with the State Department. A.J. served as close friend and mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr., and his wife, Coretta Scott King.

But it was with the onset of the Vietnam War and its fierce popular opposition that A.J. entered what may have been the most active period of his life. He alone was trusted by all the radical groups, he alone was able to act as the center around which they could organize the vast coalition of energies which became the American movement to end that war. In 1966 he led a group of pacifists to Saigon, where after trying to demonstrate for peace, they were arrested and deported. Late that same year, he flew with a small team of religious leaders to Hanoi where they met with Ho Chi Minh. Old men meeting in the midst of war, one of them committed to the path of violent change, the other to nonviolence. Less than a month later, A.J. died suddenly in New York City. At his death messages of condolence came from sources as diverse as Ho Chi Minh and Robert Kennedy.

Memorial services brought speakers from the Church, the Trade Union movement, and from both the Communist and Socialist Workers Parties. To an outsider it must have seemed incomprehensible that a single man could have so broad a range of friends. To his associates he was a remarkably warm person, one who loved baseball and poetry. To audiences, however, he seemed more distant, and while his speaking style was direct and immediate, one listener said she knew, having heard him, what the prophets sounded like. His integrity was beyond question. He tolerated disagreement but achieved remarkable loyalty. He did not have disciples but co-workers. A brilliant thinker, he left behind no single body of theoretical work--but a small army of women and men whose lives, hearts and thinking were forever radically changed by knowing him.

There are two themes that ran through A.J. Muste's life so clearly and marked his own actions so decisively, that the conflict between them became a dialectic, never resolved. One theme was peace, nonviolence, profound reverence for life. The other theme was social justice. To respect life meant to struggle to achieve social justice, yet the struggle for social justice invariably disturbed the peace and risked the nonviolence so central to A.J. The life-destroying institutions of injustice which A.J. saw around him were intolerable--yet violent social change was also intolerable. It was this "dialectic" which led him into the Marxist-Leninist movement and then back into the religious pacifist movement. Those who worked most closely with him are convinced that he was never fully able to leave behind his Christian mysticism when he was a Marxist-Leninist, and that on his return to the Church he brought with him much of his Marxism.

No authentic honor can be done to the memory of the man and his life if we select one theme and ignore the other. Few people have been so deeply committed at the same time both to peace and to social justice, so fully aware of the difficulty of reconciling these two demands, and so intent on making that effort.

One of A.J. Muste's favorite selections from poetry is surely one which he earned as a final homage:

I think continually of those who were truly great--

The names of those who in their lives fought for life,

Who wore at their hearts the fire's center.

Born of the sun they traveled a short while towards the sun.

And left the vivid air signed with their honor.

-Stephen Spender